|

Erinnerungen britischer Kriegsgefangener an das Lager Elsterhorst |

|

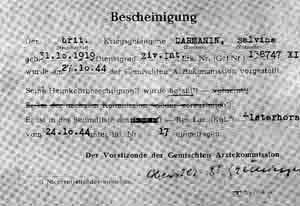

| Quelle: | Manuel Darmanin "Our Father Who is in Heaven, had His Own Plans for me" |

| in Auszügen erschienen auf | |

|

"Transfer to Reserve Lazarett at Elsterhorst On the 19th of the same month, some prisoners were sent to Elsterhorst, reserve Lazarett 742, Stalag IV, about 25 miles southeast of Dresden, a P.o.W hospital. Its six bare frame buildings sheltered about 150 tuberculosis patients, mostly bed-cases. German administration and their Medical Officers were not always scrupulous in taking all the necessary measures to safeguard the health of the patients. At the entrance there were six bare wooden huts, perfectly lined and surrounded by grass and sand, which looked surprisingly clean. Fortunately, medical officers from the Allied Forces, themselves prisoners-of-war, made up for the lack of conscientiousness of the German administrators and did their best to care and raise the morale of the patients. Due to the different nationalities of the patients, Fr Darmanin acted as an interpreter, mostly to the Italian and French P.o.W., whenever they needed to consult or to be checked by the English and the French M.O.’s. These fulfilled their duty very nobly and engaged themselves tirelessly for the physical and social welfare of their patients. The occupational therapies mostly appreciated were drawing and needlework. The Red Cross and the YMCA supplied a good stock of material and most of the patients succeeded marvellously in attaining good results in all sorts of needlework and embroidery. At Elsterhorst, Fr Darmanin met Abbe’ Cerisier, a French chaplain, and was glad to attend Mass daily. In the evening, together with a few French, English M.O.’s and prisoners-of-war, met in a small room to recite the rosary and other devotions. Every Sunday, a recreation hut was used as a chapel and occasionally was transformed into a hall, where shows, concerts and social evenings were held. Table tennis and bridges were quite popular. On June a local leaflet called ‘The Rag’ was produced and later changed the name to ‘Patients’ Pie’. This consisted of a typewritten sheet with news and items of some interest to the patients. Its publishing was soon frustrated by the splitting of the patients and the editorial staff following their removal to Konigswartha Hospital.

Prisoner of War Log-Book

During their confinement British prisoners-of-war were presented with a wartime log-book by the YMCA. This log-book served as a private diary in which prisoners-of-war inscribed autobiographical records on a regular, if not daily basis on their experience while in captivity. Fr Darmanin confined himself largely to the minutiae of daily life of his experience as a P.o.W. In his log-book Fr Darmanin recorded his feelings and several events he encountered, wrote prayers, drew sketches of the prison camp and also addresses of his family, relatives and friends. He also recorded all the dates of the letters/postcards he sent to his family and friends whilst trying to communicate with them.

Christmas at Reserve Lazarett 742

The thought of the approaching winter and Christmas could not but press heavily on every prisoner’s mind. So an informal committee was set up to study various plans and to hold several competitions for the prisoners-of-war. Everybody had some suggestions, but discussions to make Christmas a real event for all residing at the Res. Lazarett was the main issue. All spare time was to be from then onwards dedicated to the necessary preparations for this big event. Orderlies kept storing carefully all paper bandages, and extra orders were placed with the storekeeper. Surplus medicines and chemicals were withdrawn from the pharmacy, empty tins and paper shavings from parcels were set aside. In the first week of December the fabrication of the stored materials commenced. Dyeing of the paper bandages consisted of mixing various chemicals into a wide range of hues. Every night, bathrooms offered the spectacular sight of meters of coloured paper hanging out to dry. Full use was made of thin cardboard to make holly leaves that were drawn, cut into many shapes to provide decorations for the Christmas Tree. Empty biscuit tins were filled with sand and branches of pine trees were implanted in them. Patients helped by folding coloured bandages into three or four coloured streamers, others gave a hand in sewing costumes for the pantomime that was being rehearsed. On the morning of December 22 the Chefartz (the German doctor in care of the hospital) left for his Christmas vacation. The wards were suddenly transformed into comfortable and nicely decorated wards. A huge Christmas tree occupied the centre of every hall. The necessary preparations were finally completed and on Christmas Eve, at 6.00p.m. typewritten programmes were distributed. A group of orderlies toured all the wards singing familiar carols. An hour and a half later, Santa Claus dressed in his traditional red costume, escorted by a British Lieutenant-Colonel, the doctors and the padre, visited the wards, shaking hands with each patient, handing small gifts and heartened all the prisoners that next Christmas would be celebrated with their families. At 9 p.m. midnight Mass was held for the Catholics. The recreational hall was packed; patients on stretchers and a great number in deck chairs were placed at the front, all smiling at each other as the Mass began. When the moment of the Holy Communion came, everyone said a heartfelt prayer for their relatives. At the end of the service a few carols were sung and then all hurriedly retired to their quarters, as curfew started at 10 p.m. On Christmas Day, everybody woke up exchanging Christmas greetings in English, Italian, Dutch, Serb, Hindi and other different languages. Breakfast, which consisted of porridge, a thin slice of bacon and a roll, was served. Meanwhile doctors were in the wards presenting Christmas cards, hand-drawn or painted by the prisoners themselves. Dinner consisted of onion soup, a small portion of meat, peas and potatoes, jelly and cookies. Considering the usual daily carrot soup and a slice of bread for months and months, this was indeed a good meal. In the evening at 6 p.m. an interdenominational service was held. Boxing Day was marked by a performance of ‘Harem Scarem’ a pantomime, produced by a young English Officer. On 1st January 1945, an ‘Arts and Crafts’ Exhibition’ was successfully held, which enlisted 285 exhibits: fretwork, woodwork, silk-work, linocut, straw baskets, fancy work, leather work, sketches, cartoons, paintings and a collection of beetles. A few days later, rumours that another exchange of prisoners-of-war and Civilian Internees were officially confirmed on the 13th January. Although entitled to repatriation, together with a few others, the German officials intentionally excluded Fr Darmanin from the repatriation list, without being given any reason whatsoever. Four days later, 200 prisoners-of-war left the camp for Switzerland. Patients, mostly stretcher cases, suffering from pleurisy, pneumonia and other diseases, had to lie for a great while in the cold and dark night on a thick layer of snow, awaiting transport. After passing a remark on how slow and carelessly this exchange of prisoners was being undertaken, the German official transferred a doctor to a punishment camp. The Advance of the Russian ArmiesIn February 1945, with the advance of the Russian Armies from the East, the prisoners were ordered to evacuate the camp, Dresden 25 miles to the west, was totally destroyed by 773 RAF Lancasters and B-17 American Flying Bombers, 25000 died. For days, long streams of horse-carts carrying children, women and old men passed wearily by the hospital, towards unknown destinations. Then from Oflag IVD, a nearby camp, about 5000 French prisoners marched by, pushing wheelbarrows and carrying their belongings towards central Germany. On the 18th of February, a friend of Fr Darmanin rushed in the recreation hut, shouting that orders had been given to evacuate the hospital by 5.00 p.m. It was already 11 o’clock. Being used to sudden moves, the prisoners hurriedly packed their few belongings, took from the storeroom as many Red Cross parcels each one of them could carry and at 5 o’clock they marched past the camp gate. It was their first step homeward bound. This time only horse-carts were available and they were strictly reserved for the most seriously sick patients. At the railway station, a few miles away, they found five cattle wagons already waiting for them. They were promptly cleaned by the orderlies and covered with straw mattresses. The patients were then assigned 40 to each cattle wagon and all could at least sit down. The following day the train moved westward at a slow pace and in the evening they reached Bautzen. The journey of 240 kilometres was supposed to be covered in three days, but because of the continuous air raids, a great deal of time was spent idling in different stations and so the journey lasted seven days. On reaching Chemnitz, which already had been the target of violent bomb attacks, the train had to stop because of an air raid, but 20 minutes later, it transpired that it was a false alarm. At three o’clock in the morning on the 26th February, the train proceeded to Hohenstein-Ernstadt. At the station a lorry was at the disposal of the seriously sick cases and the rest had to march to the hospital. The hospital, originally a convent and sanatorium, was overcrowded and before they could set foot in it, a German warrant officer ordered them to stop and turn round. Only the eight worst cases were admitted and had to stay on their stretches in a narrow and filthy corridor. The rest, about 90, had to march another 5km to a Gast-Haus (guesthouse), where only eighteen beds were available, so most of them, including patients, had to sleep on the floor. Fr Darmanin did not stay there very long, but soon learned what had been and was still going on in the main hospital: Four American soldiers, all pneumonia cases, were neither examined not attended to by any doctor for four consecutive days, and passed away in a short time. The hospital wards were crammed, covered with dust and very unhealthy. Severely wounded soldiers with amputated arms or with plastered legs were trying hard to light a fire or toast a slice of bread. People affected by gangrene in their feet had to lie in the midst of such unpleasant surroundings waiting hopefully for some kind of medical attention. After a few days, Fr Darmanin, along with a few others, was sent to a small working camp not far away. Knowing that the war was now approaching its end, the uncertainty of the future was still on their minds. Soon they started marching from one place to another and as the Russian artillery was advancing, the German military vehicles were retreating amidst great confusion. Finally the working party settled in an abandoned small paper factory. During the day they lived outside and at night sought refuge within the factory, sleeping between the paper machines. ..." |

|